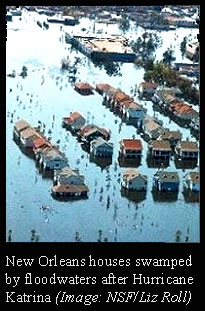

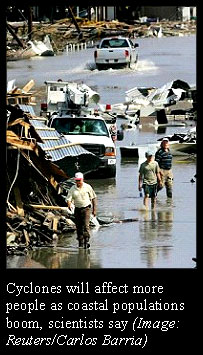

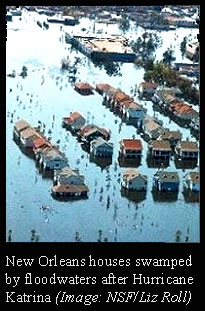

In the year since the levees broke in New Orleans, scientists and engineers have found a lot of reasons for hope and despair about the future of Louisiana's coast.

The good news is that the solution may be in the Mississippi River itself.

The bad news is that some coastal areas, including New Orleans, could be sinking a lot faster than expected. Maybe too fast. Or maybe not.

First there's that murky Mississippi water. Mark Twain, who had a stint as a Mississippi riverboat pilot, reported that a glass of the fresh muddy river water was once considered "wholesomer to drink" than clear water of the Ohio River on account of the "yaller" mud.

In fact, each year the great river carries about 100 million tonnes per year of silt, sand and gravel through engineered channels, past New Orleans and into the depths of the Gulf of Mexico.

That's equivalent to 10 Superdomes packed tight with dirt, each year, says Denise Reed, professor of geology and geophysics at the

University of New Orleans, who has been working on finding solutions for the coast.

Year in and year out, 100 million tonnes adds up to a whole lot of real estate flowing freely right into, then right out of, a place that is losing land at more than 120 square kilometres each year.

"Here we are, going cap-in-hand to Congress for money when our most valuable resource is being wasted," Reed says.

If, instead of being artificially channelled to the southernmost tip of the Mississippi Delta and dumped into deeper waters, most of that muddy water sediment were allowed to flow into the shallow surf zones further north, it would get caught up in the never-ending shoving match between the river and the sea.

Once there, as is the case along any shoreline near a river, ocean waves would serve as nature's free earth-moving machines and build up beaches that could protect the land from storm surf.

It's the very process that built the Louisiana coast in the first place, Reed says.

"The mother lode is still being wasted," she says. "We have got to keep it in the shallow water."

Muddy process

Muddy processSo just what kind of project would keep that liquid real estate in Louisiana, while at the same time protecting homes and cities, maintaining a navigable river and restoring the troubled Mississippi Delta wetlands?

That question is now the focus of feverish discussion and planning by Louisiana's brand-new Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, or CPR Authority, says Robert Twilley, a professor of wetlands biogeochemistry at

Louisiana State University (LSU).

Back in November, just two months after Katrina, the Louisiana State Legislature created the CPR Authority by blending together the state Department of Natural Resources and the state Department of Transportation and Development.

What this means, says Twilley, is that for the first time protection, which usually means buildings, is being integrated with restoration, which usually refers to coastal wetlands.

For decades the two goals have been largely perceived as opposites.

"It completely changed overnight our bedfellows," says Twilley. "It really has, in the last year, focused a very clear discussion on levees and wetlands as an integrated protection system."

The CPR Authority's first daunting task is to work with the various levee boards and the federal government to craft a comprehensive protection and restoration plan for the Louisiana coast.

The plan is to be gleaned from vast amounts of data and delivered to the public in January, Twilley says.

Muddy mysteryOne of the most slippery and yet fundamental aspects of all that modeling and planning is figuring out subsidence, or just how fast the Louisiana coast is sinking and whether there is anything we can do about it.

Just as Katrina struck last year, scientists were in the midst of a stormy debate over subsidence, Twilley recalls.

Rates of subsidence now range from just less than a millimetre per year to 170 times that rate.

Geologists know of at least three things that could be causing the ground to sink lower along Louisiana's coast.

One is the extraction of oil, gas and water from the ground, which was implicated last year in a

US Geological Survey report.

Another is the somewhat limited natural settling and compaction of river sediments that make up the ground.

Lastly, there are deeper 'tectonic' changes involving the rising and falling of shifting large blocks of real estate along faults, the sort of thing that's more common in fault-ridden places like California.

In April, Twilley's LSU colleague Professor Roy Dokka came out with a paper in

Geology, in which he argued that faulting and what looks like a gigantic, slow-moving regional landslide is the cause of almost three-quarters of New Orleans' subsidence.

Dokka revised regional elevation data using precision Global Positioning System equipment and discovered a higher rate of subsidence over the past 50 years is almost all caused by this tectonic movement.

Then in July

Geology published a paper by

Tulane University's Associate Professor Torbjörn Törnqvist, who used an entirely different approach.

Törnqvist surveyed long-buried wetland peat layers in outlying areas to come up with entirely different and milder subsidence rates.

"I think there is a very balanced dialogue going on," says Twilley of the two studies. "I have a lot of respect for both of them."

It's just the way science works, agrees Reed, and it's not surprising, considering that the two studies are so different in methods and the places they examined, she says.

Discovering the truth about subsidence is going to take a lot more work and a great deal of time, all of which Dokka, Törnqvist and others are already investing at top speed.

Like the people of the CPR Authority, the

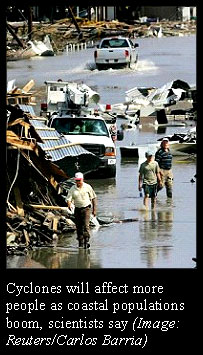

Army Corps of Engineers, the levees boards and everyone else along the Louisiana coast, the subsidence researchers are urgently looking for answers so planners can make the right decisions and everyone can get to work before another Katrina-sized storm comes anywhere near.

"The problem is," says Twilley, "it takes a lot of time, and time we don't have."

by Larry O'Hanlon

Greener Newsroom

After announcing that it would become the retailer of plans and materials needed to construct Katrina Cottages, Lowe’s joined forces with designer Marianne Cusato and Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour on Tuesday for a “board cutting” ceremony and press conference in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. During the ceremony held even as hurricane Ernesto turned onto the Florida mainland officials unveiled the first-of-its-kind Lowe’s Katrina Cottage.

After announcing that it would become the retailer of plans and materials needed to construct Katrina Cottages, Lowe’s joined forces with designer Marianne Cusato and Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour on Tuesday for a “board cutting” ceremony and press conference in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. During the ceremony held even as hurricane Ernesto turned onto the Florida mainland officials unveiled the first-of-its-kind Lowe’s Katrina Cottage. One year after Hurricane Katrina's floodwaters nearly destroyed the region, virtually nothing has been done to reconstruct the Crescent City. Inaction from local authorities, almost zero commitment from the federal government, material shortages and employers leaving workers unpaid, have all added up to a crisis of stagnation and desperation for residents trying to reestablish their lives. Rebuilding must happen, but who will do the building? Some say a new union movement is the answer.

One year after Hurricane Katrina's floodwaters nearly destroyed the region, virtually nothing has been done to reconstruct the Crescent City. Inaction from local authorities, almost zero commitment from the federal government, material shortages and employers leaving workers unpaid, have all added up to a crisis of stagnation and desperation for residents trying to reestablish their lives. Rebuilding must happen, but who will do the building? Some say a new union movement is the answer.

In the year since the levees broke in New Orleans, scientists and engineers have found a lot of reasons for hope and despair about the future of Louisiana's coast.

In the year since the levees broke in New Orleans, scientists and engineers have found a lot of reasons for hope and despair about the future of Louisiana's coast. Muddy process

Muddy process Geologists know of at least three things that could be causing the ground to sink lower along Louisiana's coast.

Geologists know of at least three things that could be causing the ground to sink lower along Louisiana's coast.

All life on this planet depends on water, a precious resource. Yet, we are struggling to manage water in ways that are efficient, equitable, and environmentally sound. Many parts of the world will face increasingly dire conditions as populations grow, cities expand, and sources of clean, fresh water disappear.

All life on this planet depends on water, a precious resource. Yet, we are struggling to manage water in ways that are efficient, equitable, and environmentally sound. Many parts of the world will face increasingly dire conditions as populations grow, cities expand, and sources of clean, fresh water disappear. If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone. The results of a recent focus group conducted by the David Suzuki Foundation reveal that most Americans are pretty hazy on just what global warming means. While they’re aware that it’s a growing concern, they’re hard pressed to say just how, or why.

If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone. The results of a recent focus group conducted by the David Suzuki Foundation reveal that most Americans are pretty hazy on just what global warming means. While they’re aware that it’s a growing concern, they’re hard pressed to say just how, or why.

The Pentagon which has long speculated on the development of robotic warriors has committed to a $127-billion project called

The Pentagon which has long speculated on the development of robotic warriors has committed to a $127-billion project called  The reason, the spill occurred when a small pinhole appeared in a 34-inch diameter pipe connecting one of BP's lesser pump fields, before the main pipeline starts south. The hole, the diameter of a pencil sprayed oil into a ditch, which slowly grew to form a small lake covering about 2 acres. The spill remained hidden covered by fresh snowfall.

The reason, the spill occurred when a small pinhole appeared in a 34-inch diameter pipe connecting one of BP's lesser pump fields, before the main pipeline starts south. The hole, the diameter of a pencil sprayed oil into a ditch, which slowly grew to form a small lake covering about 2 acres. The spill remained hidden covered by fresh snowfall.