Vampire Weed, not the killer plant from "Little Shop of Horrors

It's not the killer plant from "Little Shop of Horrors," it's real, and it doesn't wait around to be fed. Researchers have discovered that a predatory weed has a creepy trick -- it hunts down victims by their smell. This ScienCentral News video has more.

It's not the killer plant from "Little Shop of Horrors," it's real, and it doesn't wait around to be fed. Researchers have discovered that a predatory weed has a creepy trick -- it hunts down victims by their smell. This ScienCentral News video has more.A Tricky Parasite

The dodder weed may look stringy and small, but don't let that trick you. It's also known as "strangleweed" for the way it wraps around other plants. "Dodder is a parasitic plant. Many people have seen them because they look like a spaghetti mess, and you see them in yards and field and crop systems," Penn State chemical ecologist Consuelo De Moraes says. For the California tomato crop alone, dodder causes more than $4 million of damage a year according to researchers at the University of California, Davis.

De Moraes has been working with the weed, which attaches to its host plant "like a leech that will attach to the plant and then suck the nutrients out. But as a parasitic plant, you don't want to kill your host plant ... what you want to do is maintain that plant alive," she says. If that sounds more like a "vampire weed," consider that it's also practically immortal.

De Moraes has been working with the weed, which attaches to its host plant "like a leech that will attach to the plant and then suck the nutrients out. But as a parasitic plant, you don't want to kill your host plant ... what you want to do is maintain that plant alive," she says. If that sounds more like a "vampire weed," consider that it's also practically immortal."Dodder is a very difficult pest to control," De Moraes says. "The reason for that is that it attaches to the host plant, and it makes it very hard to kill the weed plant without killing the host."

"There are really no reliable ways to control this weed, short of using a flamethrower," fellow researcher Justin Runyon says. Dodder can reduce agricultural productivity and can render a seed crop unmarketable since it's hard to separate it from its host plant.

Working with Mark Mescher, Runyon and De Moraes studied how the weed finds its prey. As they published in the journal Science, they found that dodder seedlings of the Cuscuta pentagona species can target a tomato plant and grow towards it 80 percent of the time. Previously, researchers thought that the weed grew randomly until it found another plant. De Moraes' lab suspects that the weed is using chemical signals to pinpoint its meal.

Working with Mark Mescher, Runyon and De Moraes studied how the weed finds its prey. As they published in the journal Science, they found that dodder seedlings of the Cuscuta pentagona species can target a tomato plant and grow towards it 80 percent of the time. Previously, researchers thought that the weed grew randomly until it found another plant. De Moraes' lab suspects that the weed is using chemical signals to pinpoint its meal.In another experiment, the Penn State researchers found that the dodder weed can make choices. "If you give wheat to [dodder] but not anything else, they will grow towards wheat, because it's better to have something than nothing," De Moraes says. "If they have an option between tomato and wheat, they will grow towards the tomato."

"Here we have a plant that's moving, it's acting, it's searching for a prey, you could say, much the same way as we think animals do," Runyon says.

But to confirm whether the weed was using chemical signals or other types of clues, the researchers placed the weed in a controlled environment. Physically separating the weed from the other plants, the researchers placed the dodder seedling in the middle of two plastic pipes, each leading to a plastic box containing a plant. Without being able to respond to colors or other visual signals to figure out where to go, the seedling was still able to grow towards the scent of the delectable meal. One experiment had a real tomato plant in one box, and a tomato plant made out of felt fabric in the other.

The researchers also isolated tomato plant odors to test if the dodder weed would grow towards them. "Plants produce and emit these small chemicals that are picked up and carried in the air, and these are called volatiles. If you've ever been around someone mowing the lawn, that fresh cut lawn smell, those are volatiles," Runyon says. We even use volatiles for chemical signals of our own -- as ingredients for commercial perfumes.

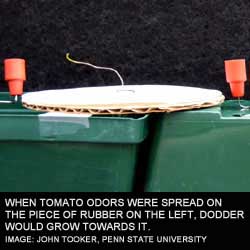

When the researchers isolated tomato plant volatiles and smeared them on the piece of rubber, dodder tried to attack that. Seventy-three percent of the seedlings headed toward the piece of rubber with tomato chemicals compared to a plain piece of rubber. While the dodder weed doesn't have a nose, De Moraes theorizes that the weed has special receptors that can detect those chemicals. "They don't have any leaves," she says, "we believe that they have receptors that perceive the smell of those airborne chemicals and then they are growing towards the host plant."

When the researchers isolated tomato plant volatiles and smeared them on the piece of rubber, dodder tried to attack that. Seventy-three percent of the seedlings headed toward the piece of rubber with tomato chemicals compared to a plain piece of rubber. While the dodder weed doesn't have a nose, De Moraes theorizes that the weed has special receptors that can detect those chemicals. "They don't have any leaves," she says, "we believe that they have receptors that perceive the smell of those airborne chemicals and then they are growing towards the host plant."But dodder's sniffing skills can be turned against it. The researchers isolated a chemical in wheat that repels dodder. This could lead to new ways of fighting the weed. "So some of the findings from this study can generate some new ideas how to deal with these pest species," De Moraes says.

De Moraes says we shouldn't underestimate the complexity of plants. "We have this sense that plants are static," she says, "that they're not doing anything. But really ... watching those plants you get this incredible sense of animal-like behavior, and you have to appreciate how sophisticated some of those interactions are."

Runyon, Mescher, and De Moraes published their findings in the September 29, 2006 issue of Science. Their study was funded by the David and Lucille Packard Foundation and the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation.

by Victor Limjoco

Greener News Room

ScienCentral News

keywords:: Vampire Plant Parasite Predatory Weed Chemical Nutrient Strangleweed

11:04 AM

<< Home